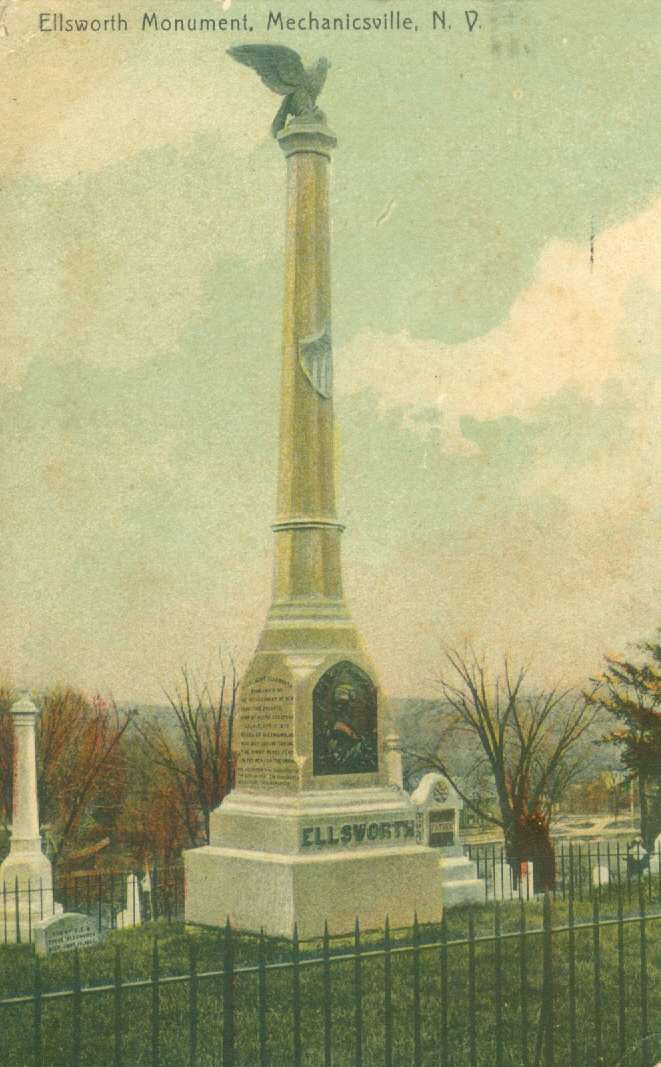

Col. Elmer Ellsworth Monument

Hudson Cemetery

Mechanicsville, New York

The election of Abraham Lincoln and the subsequent deteriorating national political scene saw seven southern states declare for secession and withdraw from the Union. A few weeks later on April 12, 1861 a lone cannon placed on the seawall of Charleston’s Battery boomed its shot across the harbor and signaled the opening act of the American Civil War. This lone shot was soon followed by intense fire from other guns aimed at Fort Sumter. Although Fort Sumter itself was not that important militarily the cannonading could only be viewed as a direct challenge to federal sovereignty and demanded a response. Lincoln immediately issued a call for 75,000 volunteers.

Among those who answered the call for 75,000 volunteers was Elmer Ellsworth of Mechanicsville, New York. A young man of 24, Ellsworth had moved to Rockford, Illinois in 1854 and ultimately chose to be a lawyer. In 1860 he moved to Springfield to study and read law in Abraham Lincoln’s law office. Active in Lincoln’s presidential campaign in 1860, Ellsworth accompanied Lincoln to Washington in 1861. With the coming of war, Ellsworth returned to New York State and recruited the 11th New York Volunteer Infantry comprised of members of New York City’s many volunteer firefighting companies. Becoming their colonel, Ellsworth equipped his new troops in the uniforms of colorful French Zouave style and soon arrived back in Washington as one of the first units responding to the President’s call for volunteers. As other units flowed into Washington the city took on the appearance of an armed camp, but no hostilities ensued.

On May 23rd Virginia elected to join her fellow southern states in secession and left the Union. Without leaving the White House Lincoln within hours of Virginia’s secession could see a large Confederate flag flying in downtown Alexandria located just across the Potomac. On May 24th Lincoln ordered federal troops across the river to occupy Alexandria and other nearby towns. As part of the occupation force Ellsworth and his regiment boarded two steamers and landed at the public docks in Alexandria and moved to secure the railroad station, telegraph office and other significantly important sites. While riding in the streets of Alexandria performing his duties Ellsworth spied a large Confederate flag flying above the Marshall House Inn. Its presence should have not come as any surprise in that Alexandria was now a city in a Confederate state. Believing it might have been the flag seen by Lincoln from the White House, Ellsworth was determined to take it down. It was a foolish act far beneath what a colonel in command of troops should have been doing. If the presence of the flag was that offensive a squad of soldiers led by a sergeant or a lieutenant would have sufficed in removing it. Instead Ellsworth with boyish enthusiasm took four men, entered the hotel and rushed upstairs to cut down the offending banner. As he was returning to the lobby Ellsworth was met at the foot of the stairs by the inn’s owner, James Jackson, an ardent successionist who killed Ellsworth at point blank range with a single shotgun blast to the chest. One of Ellsworth’s accompanying privates, a Francis Brownell, then immediately killed Jackson with a single musket shot to the forehead. As he fell Jackson was repeatedly bayoneted.

Under other circumstances Ellsworth’s death would have been little more than a footnote in history. He was, however, a friend of the President, and he immediately became a martyr as the first slain commissioned officer in the Civil War. His death and the subsequent outpouring of outrage and hostility towards the South proved more important than Fort Sumter in directing a federal response to the new Confederacy and bringing on total war.

Lincoln was deeply saddened by the loss of his friend and ordered his body brought to the White House. His troops wrapped his body in a sheet and returned him to the ship that had brought him to Alexandria just hours before. By now feelings were running so high among those who stayed behind in Alexandria that the War Department ordered the remaining members of the 11th New York confined to one of the docked ships fearing that under cover of darkness they would burn the entire city.

Ellsworth’s body was brought to the White House to lie in state in the East Room. Two days later the lines of mourners showed no slowing. The planned funeral was delayed for hours until finally a funeral cortege moved down Pennsylvania Avenue toward the depot. Rank after rank of infantry led the way followed by the hearse and more troops and ending with a carriage carrying the President and some cabinet members. Placed on a waiting train Ellsworth was transported first to New York to lie in state at City Hall and then onto his boyhood home of Mechanicsville where he was buried in Hudson View Cemetery below a 25 foot tall column monument.

The effect of Ellsworth’s death on the nation was profound. Viewed as a hero of the republic Elmer Ellsworth’s death gave birth to a national fervor that demanded revenge. His death provided front page coverage in scores of newspapers while photographs and lithographs of the young hero were published by the thousands. The cry to “Avenge Ellsworth” became a national rallying cry that brought thousands of young men flocking to the recruiting stations. Elmer Ellsworth had died not on the battlefield but on the streets of Alexandria. Friend to the President and unknown colonel, he had achieved martyrdom at age 24 by a simple but rash act to tear down a flag from its halyard.