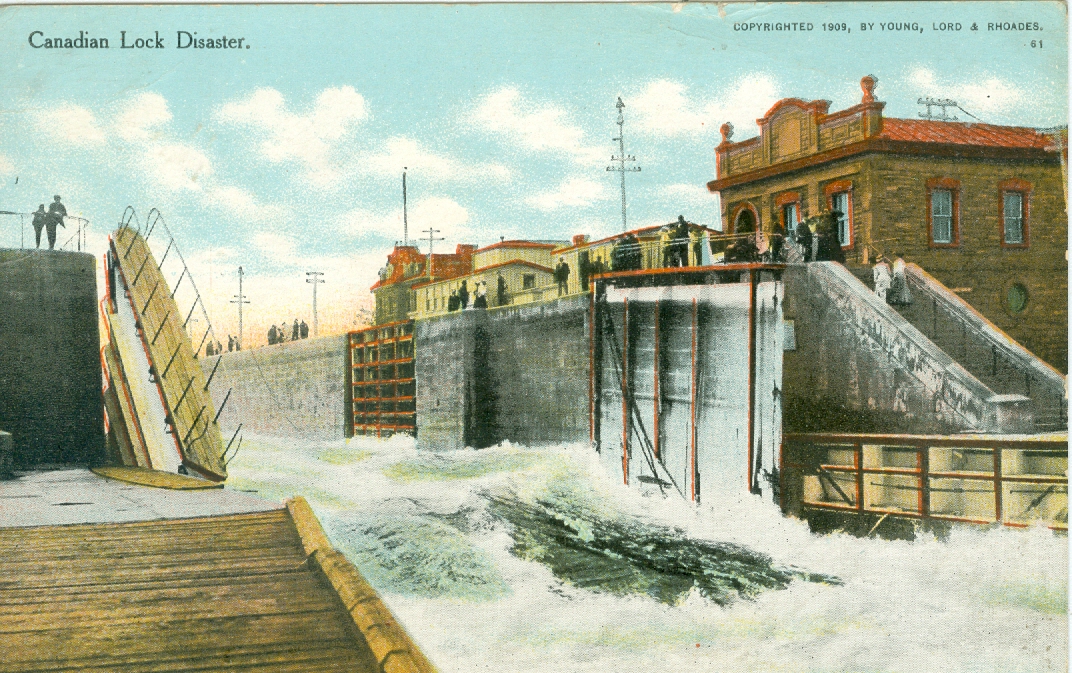

Disaster at the Canadian Soo,

June 9, 1909

For almost two centuries ship movement between Lake Superior and Lake Huron was impossible due to the swift rapids of the St. Mary’s River connecting the two lakes. A drop of 21 feet required that ships tie up and land transfer cargo to waiting ships on the other side of the rapids. That fact allowed the twin cities of Sault Ste. Marie (Michigan and Ontario) to grow and prosper with warehousing and freight handling facilities. However, it added considerably to the cost of moving freight and remained a hindrance to the movement of large bulk cargos such as grain and iron ore.

In 1855, the problem was remedied with the construction and opening of a canal lock bypassing the rapids. This original lock called the State Lock was constructed by the State of Michigan on the American side of the border. As traffic grew the need for a second lock was recognized but Michigan lacked the resources to build it. Turning to the federal government, control and operation of the canal was surrendered to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. A second lock was then constructed in 1881 and named the Weitzel Lock after its designer, Maj-Gen. Godfrey Weitzel. This new lock provided immediate improvement for transit of both upbound and downbound ships but soon proved insufficient due to increased traffic volume. Thus, in the mid-1890s both the U.S. and Canadian governments undertook construction of two additional locks to be located on both sides of the border. The Canadian Lock completed first in 1895 was followed by the Poe Lock on the Michigan side in 1896. Both were soon favored by the major shipping companies during heavy traffic periods due to their increased length and depth compared to their predecessors. There things stood for more than a decade until June 9, 1909.

June 9, 1909 dawned uneventful enough but a mid-afternoon accident in the Canadian Lock caused by an American ship disregarding lockage instructions brought traffic to a standstill and closed the entire area to maritime traffic for twelve days. That it was only closed twelve days and that no lives had been lost in the day’s chain of events was judged to be nothing short of a miracle.

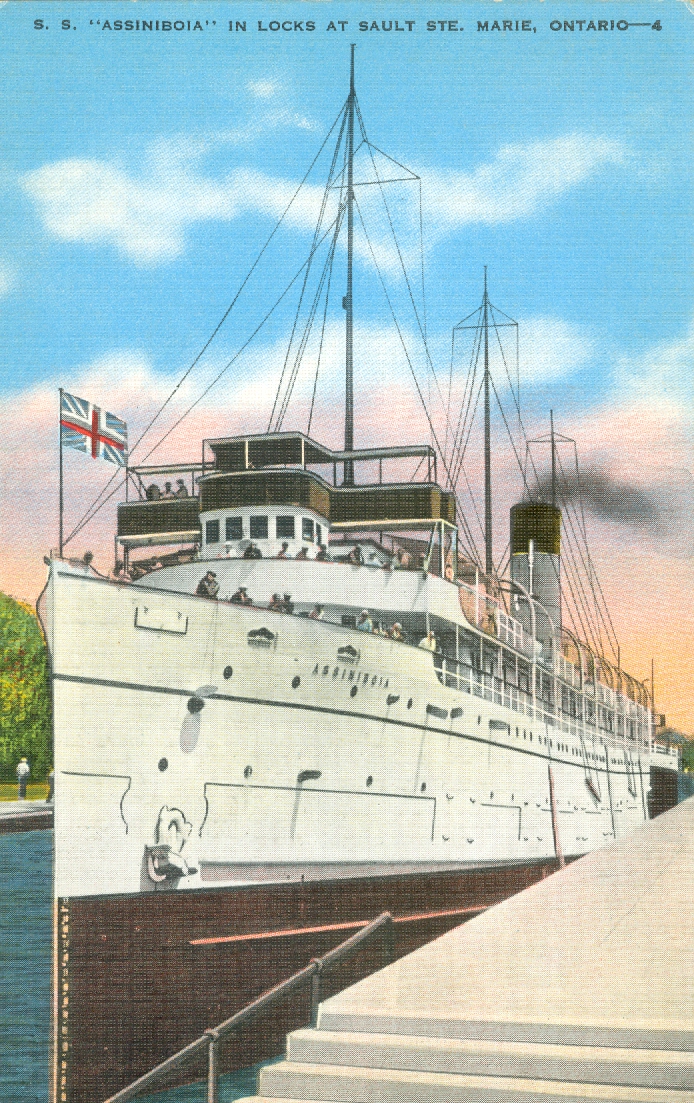

The accident involved three ships. The first was the Canadian Pacific passenger steamer Assiniboia downbound from Lake Superior. Granted passage, the Canadian flagged Assiniboia had entered the Canadian Lock and tied up for lowering. A second boat carrying iron ore, the American flagged Crescent City, was then cleared to enter the lock behind the Assiniboia. Traffic that day was heavy and the main river channel on the lower end was clogged with ships promising delays of several hours for all upbound traffic. It was at this time that a third ship entered the picture, an upbound American flagged ore boat, the Perry G. Walker. Its captain chose not to wait out the delay and opted for what he thought would be a quicker passage using the Canadian Lock once the Assiniboia and Crescent City had cleared . The Walker weaved its way through the waiting ships on the river to the Canadian side and soon received orders to tie off at a wharf and await clearance. The captain ignored the instructions and attempted to move closer to the lower end lock gates in an effort to seize the first position in line. As the Walker steamed ahead, remaining distance was misjudged and the captain ordered the engine room to reverse speed. The order was apparently misunderstood by the chief engineer who subsequently set speed at all ahead full. The Walker surged ahead in the rapidly diminishing length of open channel and struck the lower gates head on. The impact of the Walker’s collision crushed the lower end gates resulting in a pressure surge within the lock. That pressure buckled the still open gates on the upper end as thousands of tons of Lake Superior water began cascading through the lock. After the collision the Walker was forced backward by the on rushing water and had its bow turned to port. The Assiniboia was ripped free from her moorings, and while tossing back and forth off the lock’s side walls, exited the lock to strike the now turned Walker at mid-ships on her starboard side. The Crescent City meanwhile was futilely attempting to tie off mooring lines on the upper end but failing to do so was carried forward banging against the lock sidewalls as had the Assiniboia before her. After striking the Walker the Assiniboia, now free of the lock and in the main channel of the river, dropped anchor in an attempt to slow her own downward rush. That action caused the Assiniboia to swing to starboard. The oncoming Crescent City, now also free of the lock, had its captain execute a full speed astern that succeeded in turning the ship enough that it struck only a glancing blow to the Assiniboia’s starboard side with somehow the stern missing the Walker to port. Regaining control, all three ships headed for the American side for docking and damage inspection. The Crescent City, the most heavily damaged of the three, made it to a dock but sank soon after.

Damage to the Assiniboia and the Walker did not prevent a resumption of their respective trips and both were allowed to continue on their way after safety inspections were complete. The Crescent City was left behind but was eventually raised off the bottom and using compressed air in her holds managed to stay afloat long enough to reach Lake Erie to unload her cargo of iron ore and then enter a shipbuilder’s dry-dock to seek permanent repairs.

The Canadian Lock was a mess. Water continued to surge through from the higher Lake Superior and eventually carried away the gates on both ends. After several hours an emergency swing dam was successfully used to slow the current and eventually the lock was sealed off. Water was then pumped out to reveal massive damage to the gates, walls, grates and intake valves and lock timbers. Electrical wiring had been torn loose and tons of silt and debris clogged the lock and river channel. Either the Assiniboia or the Crescent City had also struck and destroyed the lower end sill leaving the lock.

Views #1 and #3 show waters cascading into the upper end of the lock from Lake Superior.

View #2 shows the broken and hanging lower gate with water surging out of the lock into the St. Mary’s River.

All traffic was, of course, rerouted to the American side. The Canadian government immediately undertook the rebuilding of the lock. Delays were unavoidable due to the sheer number of ships requiring passage through the two remaining locks and reduced navigation space in the river due to numerous dredges doing work in the main channel below the locks. Repairs commenced immediately with crews working round the clock and twelve days later the Canadian Lock was reopened to traffic. Considering the extent of the damages and the equipment on hand to effect repairs, absolutely no one had expected a reopening in just twelve days.

The Walker’s owners and her captain were held responsible for cost of repairs. Eventually the owner’s insurance company paid a settlement to the Canadian government in excess of $55,000, not a small sum in 1909. It is unknown whether additional damages were ever sought or collected by the other two ships involved in the collisions below the lock.

Postscripts…

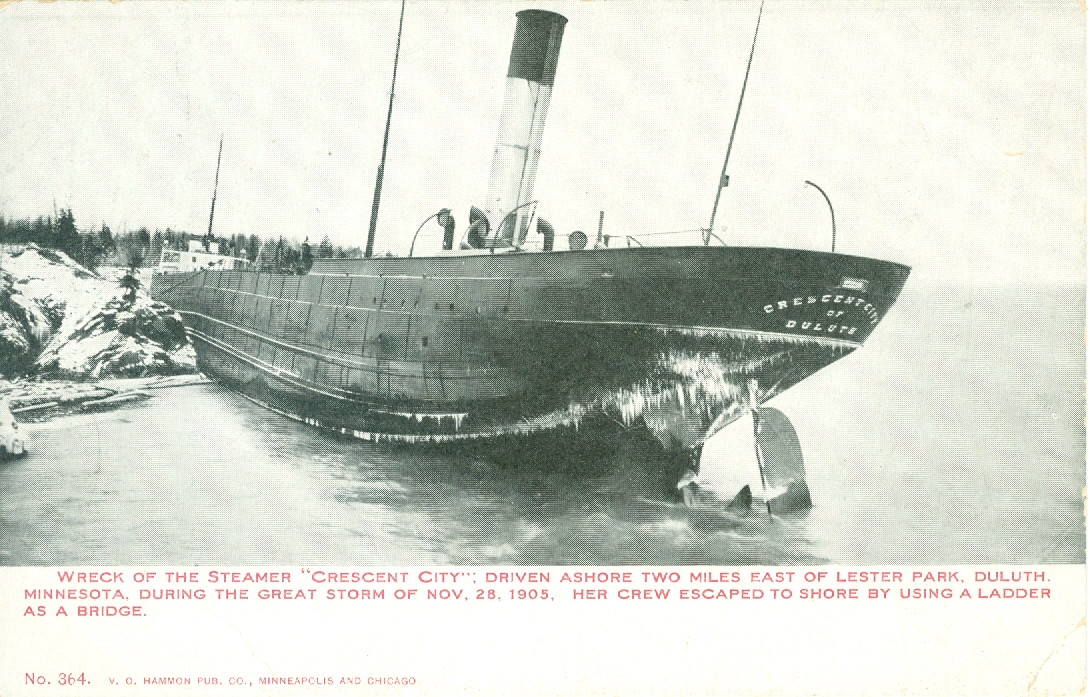

Although not responsible for the sequence of events that characterized the disaster at the Soo in June, 1909, the Crescent City could perhaps be called a bad-luck ship and had somewhat of an ill-fated career in Great Lakes service. Involved in numerous collisions and groundings, perhaps the most famous and hazardous of which was her being literally tossed ashore near Duluth in the famous December, 1905 Mataafa Storm, preceding by four years her sinking at dockside in 1909 at the Soo. Built originally in 1897 as a bulk carrier she was rebuilt in 1928 to carry automobiles to market from the Detroit area assembly lines. Anything that could float and carry bulk cargoes was used to transport iron ore during the World War II years. Crescent City was converted back to handling iron ore for the war effort. Still operating at the end of the war she enjoyed a few more years of service until 1959 when she was scrapped.

The Perry G. Walker was originally built in 1903 by Chicago Shipbuilding as a 436’ bulk carrier for the American Shipbuilding Company in Cleveland. She was subsequently sold to Gilchrist Transportation and home ported in Fairport Harbor, Ohio. Gilchrist filed for bankruptcy in 1910, the year after the accident and the Perry G. Walker was again sold (this time at a bankruptcy auction in 1913) and renamed Taurus. She remained in service and saw regular use as an ore carrier during the World War II years. As the war wound down and iron ore demand somewhat abated from the peak war years of 1942-1943 Taurus was retired at the end of the 1944 shipping season and scrapped two years later in 1946.

Assiniboia, built in 1907 just two years prior to her accident at the Soo, saw extensive passenger service on the upper lakes through 1964. In 1965 her previous conversion to oil for fuel reprieved her for another two years in bulk cargo service before retirement for good in 1967. In 1968 she was sold with plans to tow her to Philadelphia for use as a floating restaurant. She reached National Park, NJ on the Delaware River but on August 11, 1969 suffered a disastrous fire while being converted to restaurant use. A total loss, she was refloated and cut up for scrap the following year.

As for the Soo Locks except for winter months they are still in service for all ship movement to and from Lake Superior. The World War I years saw construction of two additional locks, the Davis in 1914 and the Sabin in 1919. Most ships were by then too long for the original Weitzel Lock and it was abandoned in 1918. 1943 saw yet another lock constructed on the U.S. Side where the Weitzel Lock once operated and named the MacArthur Lock. After the opening of the St. Lawrence Seaway in 1959, the Poe Lock was rebuilt and lengthened to 1200 feet in 1968 in time to accommodate the coming of the new 1000 foot bulk carriers that now dominate movement of bulk cargoes of iron ore and coal coming down from Lake Superior. With thirteen 1000 footers in service, with air travel and Interstate highways spelling the end of passenger steamship service and with the shrinking of the American steel industry, fewer ships now navigate the Great Lakes. Only the Poe Lock can handle the 1000 footers and with overall traffic volume in decline at the Soo, the Davis Lock is used but infrequently and the Sabin Lock is presently out of service.

The 1905 Mataafa Storm, named after a ship of the same name, claimed several vessels along tbe south shore of Lake Superior extending all the way to Duluth. Above are two views of the Crescent City after being tossed ashore at the height of the storm. Refloated and repaired she returned to service to again be wrecked at the Soo in 1909.

'A third view (above left) of the Crescent City during the Mataafa Storm. Assiniboia (above right) in happier times preparing to exit the Canadian Lock on one of her many cruises from Georgian Bay to Lake Superior and return. The service lasted 60 years.

Free Lightbox Gallery