Anthracite Coal

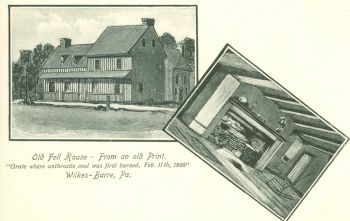

When early pioneers first explored the greater Susquehanna River Valley of Pennsylvania in the mid-to-late 18th century contact with Native Americans produced stories of black rocks that burned. Later in the century when pioneers came to stay settling above Easton and Sunbury surface outcroppings of anthracite coal were found that confirmed the truth of the stories of the burning rocks. Early attempts to harness the easily found outcroppings for heat or fuel were less than successful as it was often difficult and frustratingly slow to easily ignite and burn the coal. Many, but not all, histories credit Jesse Fell in 1808, a Wilkes-Barre tavern owner, with being the first to come up with a successful method to burn anthracite. He found that uniformly sized pieces of coal placed in a fireplace on an iron grate providing for an air flow underneath the fire resulted in an easily ignited and uniform hot burning of the coal bed. An industry was about to be born.

When early pioneers first explored the greater Susquehanna River Valley of Pennsylvania in the mid-to-late 18th century contact with Native Americans produced stories of black rocks that burned. Later in the century when pioneers came to stay settling above Easton and Sunbury surface outcroppings of anthracite coal were found that confirmed the truth of the stories of the burning rocks. Early attempts to harness the easily found outcroppings for heat or fuel were less than successful as it was often difficult and frustratingly slow to easily ignite and burn the coal. Many, but not all, histories credit Jesse Fell in 1808, a Wilkes-Barre tavern owner, with being the first to come up with a successful method to burn anthracite. He found that uniformly sized pieces of coal placed in a fireplace on an iron grate providing for an air flow underneath the fire resulted in an easily ignited and uniform hot burning of the coal bed. An industry was about to be born.

The anthracite industry that developed in Northeastern Pennsylvania encompassed nine counties and accounted for 95% of the known anthracite in the United States. By far the bulk of the anthracite was located in five contiguous counties: Northumberland, Schuylkill, Carbon, Luzerne and Lackawanna. Three of the remaining four counties, Dauphin, Columbia and Susquehanna, located at the outside edges of the main deposits, produced coal but had much smaller land areas involved in the industry. The ninth county, Sullivan, also contributed to the industry with small deposits of semi-anthracite coal being found near Bernice, Lopez, Mildred and Colley. For the next 150 years the mining of anthracite coal dominated the life and times of these nine counties from the numerous small coal patch towns that dotted the landscape to cities like Wilkes-Barre and Scranton, often referred to as the Athens and Rome of the anthracite industry.

Initial diggings produced abundant coal close to the surface especially in the northern field between Scranton and Forest City. While equally abundant coal reserves lay elsewhere in the middle and southern fields Mother Nature often did not add her cooperation in making extraction easy. Coal veins or seams seldom ran on straight uniform courses. Subjected to much folding and faulting deep underground, the mining of anthracite coal required numerous approaches to extraction including drift, slope and deep shaft mines as well as strip mining in later years often scarring the land the remnants of which can be seen to this day.

The anthracite industry fueled the industrial growth of the United States following the end of the Civil War. For some with the necessary capital investment fortunes were waiting to be made. While capital investment is a necessary part of any commercial enterprise it should also be recognized that not one single ton of coal could ever be brought to the surface without the efforts of labor.

The lot of the hard coal miner was a life of back breaking labor and drudgery beset by constant exposure to injury and death. The miners and laborers worked deep underground where the sun never shined. Poor ventilation of mines and constant dirt and dust made breathing difficult. Rock falls, mine seepage and flooding and the dangers of gas explosions were additional constant reminders of the danger of the industry, and all reaped their almost daily toll of broken, maimed or dead bodies.

Yet, men continued to go underground to mine anthracite. As thousands of families left Europe for the dream of a new life in the United States, many came to the anthracite coal fields. Few found their pot of gold and fewer still easily assimilated into American society. Seeking friendship, comfort and support among their own kind this polarization and isolation from the mainstream dominated by central European English speaking and Protestant society led to the founding of numerous towns and villages in close proximity to one another but each one settled with its own principal ethnicity, cultural background and language. No wonder that when combined with similar development in the in the coal and steel communities of western Pennsylvania that in the early 20th century the state despite being just 32nd out of fifty in area ranked No. 1 for total number of towns and communities in a state.

My family roots date to this mass migration from Europe to the Pennsylvania anthracite fields. One of my maternal great-grandfathers came first just after the Civil War. English by birth he was perhaps better educated than many from his era and he found work in Plymouth in Luzerne County as a mining engineer. My maternal grandfather, one generation removed from forebears who emigrated from Wales, grew up in the greater Scranton area. Able to speak the language but without much formal education and illiterate all of his life, he toiled as a laborer in the Cayuga mine in Scranton at the end operating a mine motor for bringing loaded cars up to the surface. The end of his mining experience came in 1929 when he was leaning out over the front end of his mine motor in a darkened tunnel hand sanding wet mine rails to improve traction. His slowly moving train collided with an overlooked empty mine car that had uncoupled in the dark when coming in on another train for reloading. Exposed on the front end of the mine motor at the point of impact my grandfather was critically injured and his right arm mangled. He was carried home and deposited on the kitchen floor, the company’s obligation complete leaving my grandmother to get medical aid. A surgeon saved the arm but not its functionality. My grandfather eventually recovered but his arm was stiff and inflexible and purple in color for the remainder of his life. Perhaps the injury gave him a few more years of life in the end by getting him out of the mines. Unemployed for a number of years he finally found work as a night watchman in a factory where he could walk a post. Following the end of his working days, death came at age 71, an age that few miners lived to see.

My paternal grandfather was probably what could be called a master miner. He learned his trade in the anthracite mines of Scotland and England beginning first as a water boy at the age of 7. When World War I started many of his friends and some cousins went to France with the various Scot highlander units. My grandfather was draft exempt because he was needed as a coal miner. Relocated to England he mined 12-14 hours a day contributing coal for the needs of wartime England. With the war ending in 1918, he returned to Scotland for a short resumption of work there. In 1922 the Depression struck Europe and the British Isles and work was hard to find. Unemployed for the first time in his life, the United States beckoned and my grandfather emigrated with his family to Pennsylvania in 1923. First a bituminous coal miner in Cambria County he relocated to Scranton in 1926 to return to anthracite mining. The rest of his career was spent in the Diamond Colliery in Scranton. With a wife and four children (including my father) he entered the mine each day because as he put it “a man has responsibilities”. His knowledge and mining skills were well respected by both miners and the company alike, but his outspoken pro-union views and his leadership among the miners alarmed management. A labor stoppage in 1939 where he was a bit too outspoken led to his being blacklisted and brought an end to his mining career. The coming of World War II brought numerous alternative job opportunities out of the mines but the years of toil underground shortened his life. Like so many of his contemporaries, he died of the dreaded black lung and lung cancer while still in his 50’s.

It was from this heritage that I first became interested in the anthracite industry. In my attempts to learn more about anthracite coal mining by often visiting the area, I first encountered visible resistance when approaching uncles that had been coal miners that thought the industry best left in the past not understanding why I would want to dig it up again. Now, with the industry gone over 50 years and most miners deceased, memories have dulled or are largely unknown among area families. For many who had family members who toiled and possibly died in the mines, none are often closer in the family tree than a great-grandfather. It seems that there is now a renewed interest in learning about the area’s heritage. Historical societies and local colleges and universities host programs. New books are being published. The state operates three anthracite museums with other smaller ones operated by county historical societies, memorial associations or in private ownership. Even a monument or two have been erected such as in Olyphant commemorating the legacy of the town and those miners who toiled underground. It is against this background that I offer my little contribution to recognizing my family’s heritage.

Collieries and Coal Breakers

Coal Breaker Postcard Gallery

- Lackawanna County

- Luzerne County

- Schuylkill County

- Northumberland County

- Carbon County

- Columbia County

- Dauphin County

- Susquehanna County

- Sullivan County

- Unidentified County

Partial List of Name Anthracite Coal Breakers and Collieries

As anthracite mining got underway it was realized that coal did not come out of a mine in uniformly sized and clean pieces. As it was blasted loose from veins deep underground, the coal fell in all sizes mixed with rock, slate, dirt and a myriad of other impurities. Before it could be sold in any form for commercial success the coal had to be washed if possible and then sized and separated from its accompanying impurities.

As anthracite mining got underway it was realized that coal did not come out of a mine in uniformly sized and clean pieces. As it was blasted loose from veins deep underground, the coal fell in all sizes mixed with rock, slate, dirt and a myriad of other impurities. Before it could be sold in any form for commercial success the coal had to be washed if possible and then sized and separated from its accompanying impurities.

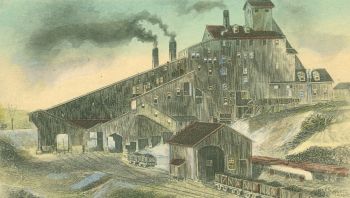

The answer lay in coal breakers which were essentially coal preparation plants housed in buildings on site often as close to the mine opening as possible for economy and ease of operation. Over the next 150 years coal breakers numbering in the hundreds spread throughout the anthracite region. Some had colorful local names; others were simply numbered. However identified the coal breaker was essential to the operation of the mine. Often dominating the landscape around the various coal patch towns, they were what I like to refer to as MONUMENTS TO KING COAL.

Postcard Sets and Series

The following buttons provide both complete and open-ended checklists of pre-1920 coal mining postcards produced by recognizable publishers from the Pennsylvania anthracite region.