Mary Jemison & Frances Slocum

During colonial times from New England to North Carolina Indian raids on outlying farms and settlements were a source of constant fear. Often conducted by small war parties moving quickly and difficult to detect, the raids would often result in the burning of homes and barns, slaughtered livestock and the killing and scalping of scores of settlers. Sometimes the Indian raiders would take captives especially young women and children. The Indian raiders would then retreat to their home areas forcing their captives to endure a march of many hardships. For those who survived the march, captivity among the Indians awaited. Many children were sold or traded to other tribes and to the French in Canada; others were adopted into Indian families. Women were taken as white squaws, many living out their lives as wives and mothers in the village hierarchy. Two such instances are illustrated by the lives of Mary Jemison and Frances Slocum, Pennsylvania girls taken captive in their youth and adopted into Indian villages where they grew to adulthood, married and became respected members of their tribes.

Mary Jemison (1743-1833) was born of Scotch-Irish stock on a ship while crossing the Atlantic that was carrying her parents and three siblings to a new life in America. Upon arrival the family, now numbering six, settled in Adams County, Pennsylvania near the present-day village of Orrtanna. Hard work and thrift and an additional two children soon allowed the family to move to a bigger farm in the nearby Buchanan Valley. When Mary was 12, the coming of the French and Indian War brought upheaval and often brutal and bloody bush warfare to the Pennsylvania frontier.

Three years later when Mary was 15 the war came to their doorstep when a band of six Shawnee Indians and four Frenchmen attacked the family farm. Rushing the farm house the raiding party took seven family members and three neighbors prisoner, plundered the house for food they could carry and then set out in great haste carrying their ten captives with them. Moving westward toward Fort Duquesne some 200 miles away they lashed and whipped the children to maintain the fast pace while denying all the prisoners any food or water. Reaching a swamp on the second night of their march, the raiders paused to rest. At some point realizing they were being pursued by the Jemison neighbors and not wishing to be slowed by captives, eight were immediately killed. The dead included all of Mary’s family excepting two brothers who had escaped detection back at the farm and were not involved in the march. For whatever reason, only Mary and a small boy (not related to the Jemisons) were spared.

The raiders eventually reached the Ohio River where Mary was sold to a party of Seneca who loaded her in a canoe and headed down the river. Upon reaching a small Seneca village Mary was clothed in Indian garb, formally adopted into the tribe and received the Indian name Dickewamis or Dehgewanus meaning pretty girl. Within a year she took a Shawnee husband, a brave named Sheninjee. The union produced two children, only one of whom survived infancy. Sheninjee then fearing that the end of warfare would mean a return of captives, decided to leave the Ohio country with his young wife and child and return to his ancestral homeland along the Genesee River in New York State. The journey was seven hundred miles with Sheninjee dying enroute leaving Mary a widow at age 19. But Sheninjee’s clan relatives accepted her and made a home for her at Little Beard’s Town near present day Cuylersville, New York. This was the heartland of the Seneca people, keeper of the Western Door of the Iroquois League. Life along the Genesee was good. She soon remarried to a Seneca chief named Hickatoo with whom she would have six more children.

Their peaceful existence along the Genesee was shattered in 1775 by the coming of the Revolutionary War. The Seneca and their sister tribes sided with the British and became the targets of American military action culminating in the Sullivan-Clinton Expedition of 1779 that laid waste to the Seneca homeland. Mary fled southward to a nearby abandoned village to escape the destruction. Hickatoo fled westward to Canada and ultimately survived to return to find his wife and children. Reunited they lived another twenty years of peace and contentment until speculators and pioneers returned in search of land.

In 1797 the Seneca ceded most of their ancestral lands in return for twelve reservations and cash payments. One of the reservations was called Gardeau and consisted of 18,000 areas. Here Mary and her family settled struggling to survive in an increasingly white, hostile world. Mary had long been fully integrated into the Seneca way of life and resisted all efforts to return her to white civilization.

Most of her white neighbors who knew of Mary Jemison respected the Seneca woman they called the “Old White Woman of the Genesee”. In 1823, at age 80, she was even interviewed by a writer who penned a little book titled “The Life and Times of Mrs. Mary Jemison” preserving for posterity details of her life among the Seneca. That same year the Seneca gave up title to the Gardeau lands reserving two square miles for Mary. She, in turn, gave up these lands in 1831 and joined surviving Seneca at Buffalo Creek Reservation near Buffalo. It was here two years later that Mary died of old age at 90 and was buried in the mission cemetery on the reservation.

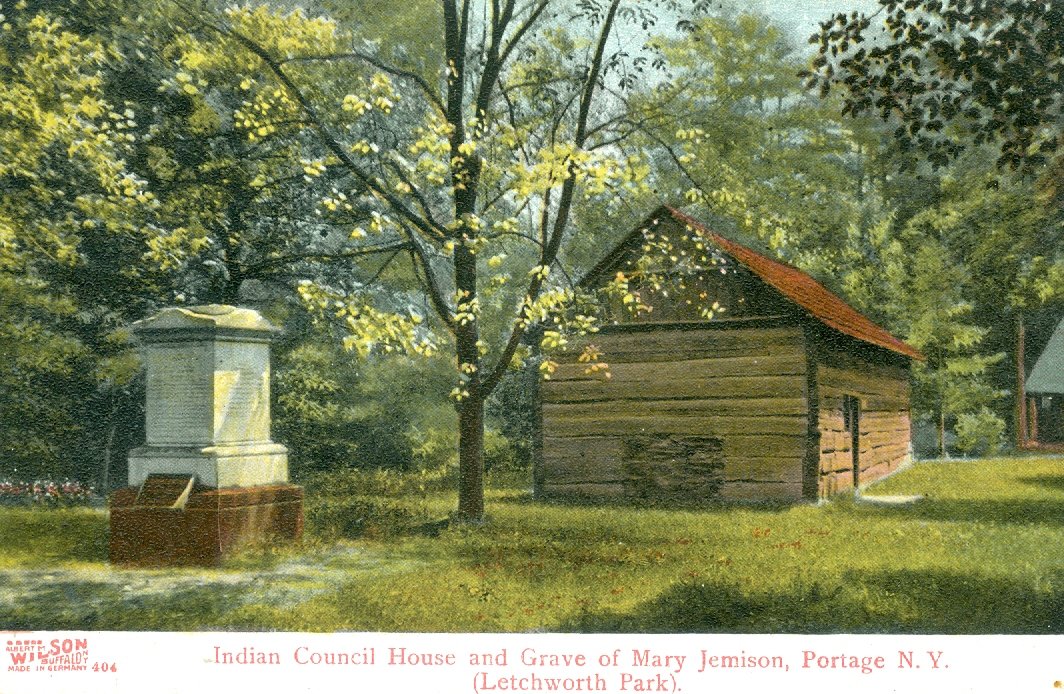

In 1874 the Buffalo Creek Reservation was sold off and the old burying ground was threatened. Her grandchildren approached William Pryor Letchworth, a major landowner back on the Genesee, to see if he could help them find a suitable resting place for their grandmother’s remains. He immediately made provision for them to bring her bones to his Glen Iris Estate located in Castile. In March, 1874 her remains were removed from her original grave, placed in a new walnut coffin and brought to the Genesee by the Erie Railroad. In ceremonies held in the ancient Council House that blended both Seneca and Christian ways, Mary Jamison was re-buried on the bluff above the Middle Falls of the Genesee.

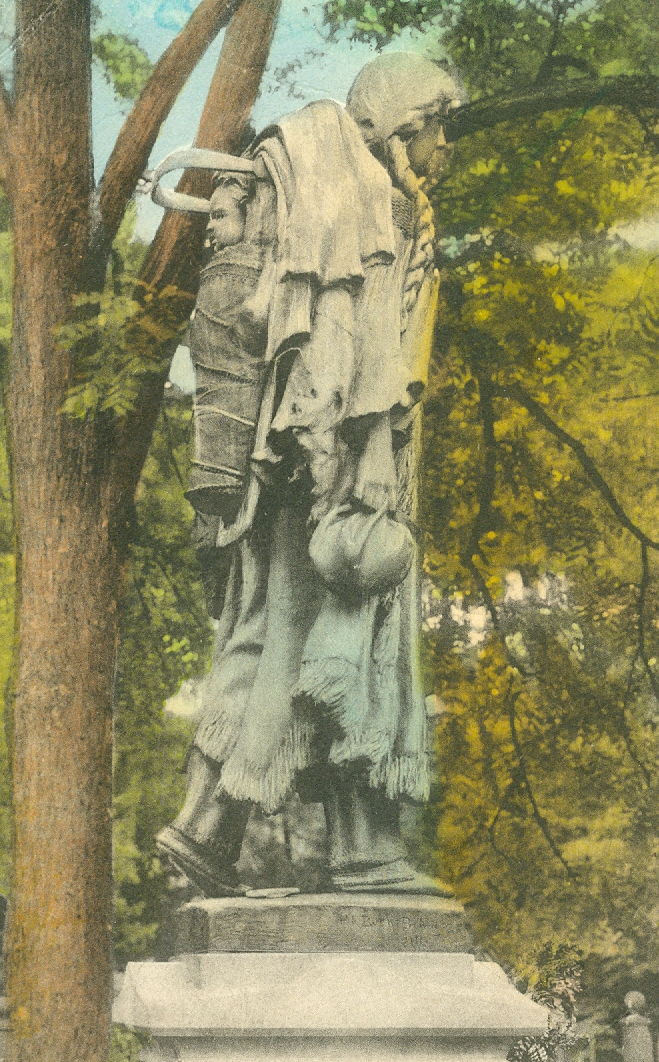

Today the Letchworth lands and the Jemison grave are part of Letchworth State Park. In 1910, Letchworth, himself, arranged for the placement of a granite marker atop Mary Jemison’s grave. It includes a likeness of Mary Jemison as a young Dehgewanus with her son on her back making the long trek from the Ohio to the Genesee. A second monument to her memory has since been constructed back in Pennsylvania’s Buchanan Valley.

|

Left: A bronze lifesize monument of Mary Jemison making the trek from the Ohio country to New York with her infant son on her back marks her present-day grave in Letchworth State Park in Castile, Wyoming County, NY.

Right: A second monument to Mary Jemison's memory is located in Buchanan Valley, Pennsylvania, site of her abduction by Indian captors in 1758.

|

|

Like Mary Jemison, Frances Slocum (1773-1847) was also stolen from her family at just five years of age by Indian raiders on November 2, 1778. This abduction took place in the Wilkes-Barre area near the location of the infamous Wyoming Massacre just four months earlier. Delaware Indians had entered the family home in broad daylight finding Mrs. Slocum and three of her children. All but young Frances managed to escape; Mary was immediately discovered hiding under a bed when the raiders ransacked the farmhouse looking for food. Taking young Frances and two unidentified neighborhood children, the Indians made good their escape and headed northward up the Susquehanna River to New York. Spending the first night in a cave south of present-day Wyalusing, the Indian captors apparently tired of the two neighborhood children due to incessant crying and killed them before the coming of daylight on the second day.

Frances survived the trek to New York and over the years adapted herself to Indian life and language while forgetting her own. Now adopted into the tribe, Frances and her new family wandered from place to place living on the Niagara frontier, then near Detroit, Fort Wayne and finally among the Miami on the Mississenewa River near Peru, Indiana.

Over the years following Frances’ abduction, her two surviving brothers who had escaped capture with their mother had searched in vain for news of her possible survival and present whereabouts checking out every reported instance of a white woman living with Indians--all to no avail.

In 1835 James T. Miller, an Indian trader living in Peru and Col. George W. Ewing, an Indian agent stationed at Logansport, were traveling among the Miami when Ewing was taken ill. Miller suggested they should stop and spend the night with a white woman who lived among the Indians. Ewing was quite surprised to learn there was a white woman living among the Miami but upon reaching her house and being kindly received, he suggested to Miller that they should find out her history and how she came to live in Indiana among the Miami. They had found this white woman in poor health and she being under the impression she had little time to live consented to the interview using Miller as an interpreter.

In her story she remembered her father as being a Quaker named Slocum who had a farm on the Susquehanna near a fort. She remembered details of the abduction and thought the surname of the two slain children to be Kingsley. She then recounted details of her life among the Indians.

Ewing, upon his return to Logansport, desired to make some effort to discover her relatives. He wrote down the facts he had learned and communicated them in a letter to the Postmaster of Lancaster, Pa suggesting they be published and circulated. The Postmaster, upon receiving the letter, thought it a hoax and tossed it aside. Fortunately, it was not destroyed and was found two years later following the postmaster’s death by his widow while sorting through family papers. Published in a local newspaper, a copy eventually fell into the hands of Joseph Slocum, a brother then residing in the Wyoming Valley near Wilkes-Barre. He immediately recognized the facts as matching those of his sister’s abduction. Contacting Col. Ewing directly, he became further convinced the white woman among the Indians was his lost sister Frances. Isaac Slocum, another brother, had left the Wyoming Valley and was living in Ohio near Sandusky. In learning of the details of the newspaper story from his brother in Pennsylvania, Isaac immediately set out for Peru to find his sister. Arriving in May, 1838 he first attempted to find James Miller, the Indian trader, who kept a store in the village. Upon receiving word that a stranger staying at the hotel wanted to see him, Miller left his store to meet this unknown visitor. Upon seeing Slocum and instantly recognizing the white man as a brother of the white woman due to family resemblance, he addressed the stranger as Mr. Slocum. Startled, Slocum asked how he knew his name and was told “by your resemblance to the white woman who lives among the Indians.”

Miller then asked Slocum if he would like to see two of the white woman’s children who worked at his store. Nodding in the affirmative a meeting was quickly arranged but the girls when told of Slocum’s identity became wary and guarded fearing he had come to take their mother away. Slocum then insisted on going to his sister’s home without further delay. Miller sent the girls on ahead to break the news while he and Slocum took a more round-about route to her home. Enroute Miller asked Slocum how he would recognize his sister and he replied that she had a lock of white hair. Miller replied that all of her hair was now white due to her advancing years. Slocum then also related how as a little girl his brother had accidentally smacked her finger with a hammer on an anvil that had pounded off its tip and nail. That mark she must still have.

Upon reaching the white woman’s home, Miller requested Slocum to wait outside for a few minutes while he went in. Upon seeing the elderly white woman and holding her hands he saw the forefinger was gone. He was now fully convinced and brought Slocum into the house.

The long separated brother and sister were soon clasped in each other’s arms. There was no reserve. Frances at once saw the family resemblance and acknowledged the relationship. She could talk but little English, but words hardly seemed necessary at that point. Isaac broke down and wept. Frances offered supper but Isaac answered he was too excited to eat. Then, communicating as best they could, they sat up next to each other all night long talking.

The next day they all returned to Peru where Isaac entertained his new found relatives. After a few days he returned home to Sandusky. Subsequently, the second brother Joseph, back in Pennsylvania, brought his two daughters to Peru to meet Mary for the first time. They endeavored to persuade Frances to return home to Pennsylvania with them, but she was completely an Indian in language, habits, associations and customs and she had no desire to leave those who had always treated her kindly and provided for her needs. Widowed twice and the mother of four children, she was now elderly, felt she had little time left to live and was content to remain among the Miami.

As frail as she was at the time of her family reunion Frances Slocum, also known as “Ma-con-a-quah”, was to live another nine years before dying in 1847. At the time of her death she was 74 years old. Her brothers helped her secure a grant of land for her surviving daughters so that upon her death the girls would be provided for. Even when the Miami were forced out of Indiana westward to the Indian Territory, her descendants remained in Indiana. Upon Frances’ death, she was buried next to her second husband and sons in the Indian cemetery near her home.

As frail as she was at the time of her family reunion Frances Slocum, also known as “Ma-con-a-quah”, was to live another nine years before dying in 1847. At the time of her death she was 74 years old. Her brothers helped her secure a grant of land for her surviving daughters so that upon her death the girls would be provided for. Even when the Miami were forced out of Indiana westward to the Indian Territory, her descendants remained in Indiana. Upon Frances’ death, she was buried next to her second husband and sons in the Indian cemetery near her home.

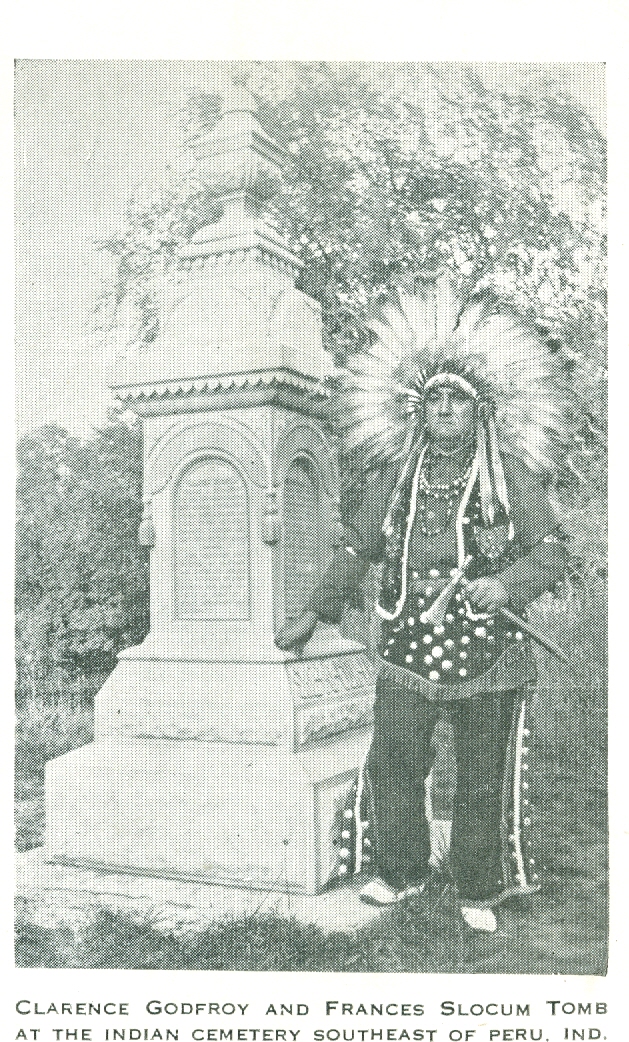

In 1900 the cemetery was renamed in her honor and on May 17th, crowds of visitors came to Peoria, Indiana to witness the unveiling of a white bronze monument atop her grave. Frances Slocum had spent her life among the Miami being known as both the “White Rose of the Miami” and the “Lost Child of Wyoming”. Inscribed upon the shaft was a history of Frances’ life as she had told it to her grandchildren. The shaft bears both the same Slocum and her Indian name “Ma-Con-A-Quah”.

Today museums in Peru contain several relics associated with her life among the Miami. A city park is also named in her honor. Indiana recognized her life naming both a Frances Slocum State Recreational Area and a Lost Sister Trail in the Mississenewa State Forest. Her monument was subsequently moved into nearby Wabash County because of the flooding of the original site by the Mississenewa Lake Reservoir, part of the Upper Wabash Flood Control. Her name is also remembered back in her native Pennsylvania in the Wyoming Valley area with a state park built around a lake and dam all named in her honor.

|

Left: Clarence Godfrey, son and grandson of Miami chiefs, poses in tribal garb with tomahawk at grave of Frances Slocum at original burial site near Peru.

Right: Frances Bundy and Mabel Rae Bundy, granddaughters of Frances Slocum, pose at original burial site near Peru.

|

|

|

|

||